Alain Farhi (July 2015)

Les Fleurs de l’Orient Honors Mathilde Tagger

by Alain Farhi

Avotaynu Volume XXXI, Number 2, Summer 2015

Les Fleurs de l’Orient, a unique website, includes a major genealogy project with more than 250,000 entries, personal documents and publications submitted by various authors, a bibliography, references, links to genealogy sites, a compilation of Franco-Egyptian words and expressions spoken and written by many French-speaking residents of Arab lands in the Middle East, plus photographs and memorabilia about the families mentioned. Its web address is www.farhi.org.

Although the genealogy project started with the Farhi families, it now covers the genealogy of the major families originally from the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. It has expanded to cover linked Sephardim, Ashkenazim and Karaite families, each with their own ancestry and descendants in their new countries of adoption. The geographical distribution of listed families covers the world from Argentina to New Zealand. Several members of the family trees have participated in a DNA study to map their migration patterns and to search for common ancestry.

For the past 15 years, primarily one person in the Jewish genealogy community assisted and guided Les Fleurs in the path of worldwide recognition: the late Mathilde Tagger (1933–2014). Mathilde was a fellow founding member of the International Institute of Jewish Genealogy (IIJG), and her efforts to promote Sephardic genealogy led me to participate in programs she organized at the 2004, 2006 and 2012 International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (IAJGS) conferences on Jewish genealogy. For several years, we collaborated on what was her trademark work: lists of names for the various countries she studied. Mathilde was instrumental, for example, in publishing, on SephardicGen.org, lists of all tombstones in the Jewish cemetery in Beirut. Until the eve of her death, she was working on lists of Jewish graduates from Saint Joseph University and American University in Beirut, these secured by a common friend, Nagi Zeidan. These lists will be published on Les Fleurs de l’Orient at a later date.

For those who may not have access to AVOTAYNU’s archives, the following is a recap of our milestones highlighting the contributions of Mathilde Tagger.

Farhi Family Genealogy

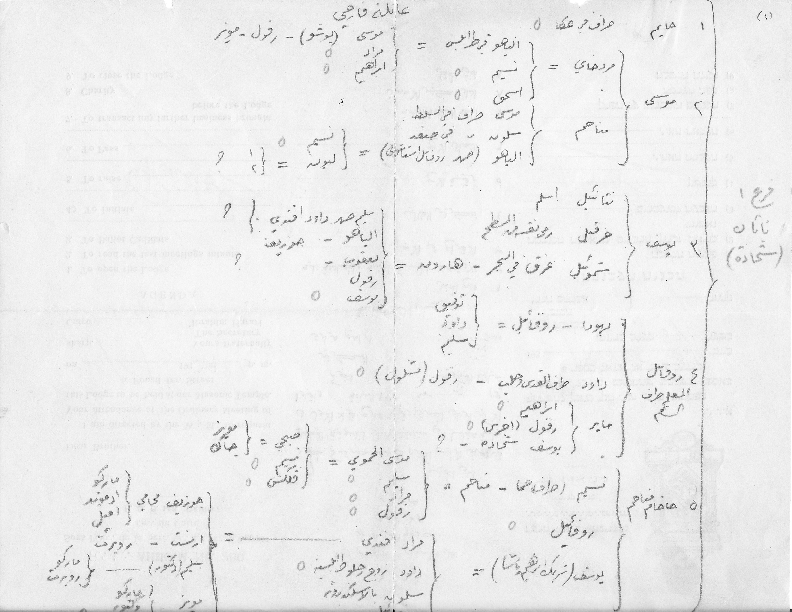

Early in my research, Tagger secured some Spanish documents that seemed to confirm the Spanish origin of all the Farhis (later disproved by a Y-DNA study). My documentation of the Farhi family began in 1979, when, after my father died, I discovered a suitcase full of documents that had come with us to New York City after our (modern-day) exodus from Egypt, where I was born. Among the surviving items were four pages handwritten in Arabic in which my grandfather Hillel (1868–1940) had drawn a family tree of the Farhi clan as he knew them (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Farhi Family Tree

In the Sephardic tradition, only descendants of the men were recorded; the daughters, once married, were no longer named Farhi and were dropped. By 1984, I had translated the first four branches into English and had drawn up a graphic tree. I mailed the trees to every Farhi I could find, some whose names I found in telephone books around the world wherever I visited, others carried by friends who also traveled.

Between 1988 and 1995, these four pages grew to 21 branches. Copies of the tree were mailed periodically to the approximately 200 participants in that effort. The 21 families were mainly people who bore the Farhi surname and who had originated in the Ottoman Empire (Turkey and Bulgaria) but were now living in Brazil, Canada, France, Israel and the United States.

In 1995, Maurice Hazan of Paris (since deceased) tracked me down. Maurice had retired and had actively developed a genealogy hobby. He had compiled a tree of about 8,000 names of the major Egyptian Jewish families to whom he was related. Because a maternal aunt was married to a Farhi, Hazan had taken an interest in the Farhis as well. His tree, fortunately, included the families of the Farhi women and their spouses. Hazan showed me, from my 1984 copies of the Farhi tree and with the help of professional British genealogists Lydia Collins and Morris Bierbrier, how he had been able to include the descendants of the Farhi women, their husbands and the husbands’ ancestry. Hazan suggested that I use the genealogy software that he used, and I moved my 21 branches away from a purely graphical representation into a database. For several years, Hazan and I cooperated on our research and kept a copy of each other’s databases. By 1998, the 21 branches—now including the Farhi women and their descendants—had grown so large that printing and mailing the updated graphics became a major challenge.

After a 1999 visit to the Goldman Center at Beit Hatfutsot, where I learned how it disseminated the Farhi data held there, I decided to publish my own tree on the Internet and allow free access to my database of about 1,200 names. I registered the domain name farhi.org and launched my website. Instead of mailing reports, I directed queries to the website.

To gain visibility, I wrote to search engine operators requesting that they list my site. One of them was the soon-to- be-born Google, of whose existence I learned when my son’s roommate went to work for the company. From early on, Google indexed the contents of Farhi.org. This early start gave Les Fleurs de l’Orient a high ranking on Google results page, which in turn brought in more genealogists to add their data. Maurice Hazan died in May 2000 before he could create his own website. In his memory and to preserve his work for others to share, I added his 8,000 names to Fleurs de l’Orient and linked them to the Farhi spouses. At this point, my genealogy effort became one big web of linked families. Both the ancestry and descendancy of any family linked to a person already existing on the site was added. As more people who were “Googling” their names found relatives on this site, they volunteered to publish their own work, and the number of persons listed on the site grew. As more trees of allied families were submitted, I created new trees on the same website. As of March 2015, more than 230,000 names were linked and published on Les Fleurs de l’Orient. Unlike most commercial genealogy sites (Ancestry, My Heritage), museums (Beit Hatfutsot) and the LDS (Mormon) Church where individuals post their own trees, all the trees and branches viewed on the Fleurs de l’Orient are linked by marriage into a giant web of families. I update and correct the trees monthly to reflect the new data that flows in and to eliminate duplicates.

Naming the Site

The name of the website, Les Fleurs de l’Orient (using also a French pun meaning the “Best from the East”), was based on the origin of the Farhi name (![]() ), which in Hebrew shares the same letters as flower (perah). L’Orient refers to their recent origins after their exodus from Spain following the Inquisition in the 16th century. In French, Les Fleurs de l’Orient also means “cream of the crop” of the Orient (families).

), which in Hebrew shares the same letters as flower (perah). L’Orient refers to their recent origins after their exodus from Spain following the Inquisition in the 16th century. In French, Les Fleurs de l’Orient also means “cream of the crop” of the Orient (families).

With the passage of time, the site has acquired more families than the original Farhi. Its domain name should have been changed from farhi.org to another one, but rebranding meant loss of Internet visibility, so I abandoned the thought.

Origin of Farhi Surname

The original “Fleur” was Ishtori, son of Moses, son of Nathan. In his 1340 autobiography, Kaftor va Perah (Bud [of a flower] and Flower), Ishtori describes the origin of the Farhi surname and other details of his life.

Ishtori was named after the town of Florenza, Spain, where his parents lived. In Spanish flora means flower, as does perach in Hebrew. Ishtori became to be known as HaParhi. The surname later became just Farhi. Ishtori was born in Florenza, a small village near Barcelona; the date of his birth is approximately 5040 by the Hebrew calendar, about 735 years ago, or 1280. He was raised in Provence (France) and studied in Trinquetaille (Arles) at the yeshiva of his grandfather Rabbi Nathan. At age 19, he studied astronomy with Jacob ben Makir in Montpellier.

After the 1306 expulsion of the Jews from France, Ishtori moved with his two brothers to Barcelona via Perpignan. After seven years in Florenza learning Torah, he decided to leave his family and home country and go to Eretz Yisrael. He traveled to Toledo and reached Cairo in 1313, where he met Maimonides’ grandson. After several years in Cairo, he traveled to Palestine and settled in Bet Shean. Kaftor ve Perah was reprinted in 1549 in Venice and in 1897 in Vienna. A modern version was published in Jerusalem in 1946 and has been translated into English under the title A History of Rabbi Isthori HaParhi. (See www.farhi. org/Documents/Rabbi_Ishtori.htm.) Isthori died in Palestine in 1357 while traveling to Jerusalem. We do not know if Isthori ever married or if he had any children. We assume, however, that his two brothers remained in Spain and that their descendants left after the Spanish Inquisition, possibly to North Africa but mainly to the Ottoman Empire, settling in Smyrna and Istanbul. We do not know how the Farhis arrived in Smyrna after the Spanish Inquisition, but we do know of a Moses, son of Nathan Farhi buried in 1609 in Istanbul’s Haskoy cemetery. In 1731, two brothers moved from Smyrna to Damascus and Istanbul, respectively. I descend from the Damascus branch. We presume that some went to North Africa in the Berber areas and later in coastal cities; Farhi families lived in today’s Algeria and Morocco. No link has been found with these families or those of the Ottoman Empire where the majority settled. From Smyrna, they fanned out to Algeria, Anatolia, Italy, Austria, Bulgaria, Egypt, Libya, Palestine, Romania, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen and Yugoslavia. Starting in the mid-19th century, Farhis traveled to Europe, North America, and Central and South America. My effort has been to trace all these descendants and, with their help, trace their ancestral lines back in time as well. From a book in her library named Sources for the History of the Jews in Spain (vol. 6, 1412–1416, page 253), Mathilde Tagger helped me find legal records of two Farhi families who lived in Zaragoza and Avila after 1465 in pre- Inquisition Spain. From results of the 2004 Sephardic Migration Y-DNA study, we concluded that all the Farhis living today may not be related to one another. In that project, we tested the Y38 DNA of two distant Farhi cousins whose ancestors lived in Syria from 1731, one from Tunisia (19th century) and four from Bulgaria/Turkey (19th century). The Syrian men showed a near perfect match. The four Bulgarians showed a perfect match indicating a common, but unknown, ancestor. The two Syrians and four Bulgarians, however, had no link to each other. The Tunisian Farhi had Y-DNA similar to two Iraqi men, Ken and Ezra Bekhor, but showed no common ancestry with the other six Farhi men. The discovery that the Bulgarians are unrelated to the Syrians disproved the theory that all Farhis descended from the same two Farhi brothers in Spain. Many men named Farhi in Algeria, Iran, Morocco and Pakistan are of the Muslim faith. These Muslim families are known to be unrelated to the Jewish families. The Arabic spelling of their surname also is different from the Jewish spelling of Farhi. More information on, and analysis of, the results of this DNA project may be found in AVOTAYNU, Vol. XXIII, No. 2, Spring 2007 or at http://www.farhi.org/files/Avotaynu_Sephardic DNA_Study.pdf .

Current Size and Distribution of the Database and Statistics

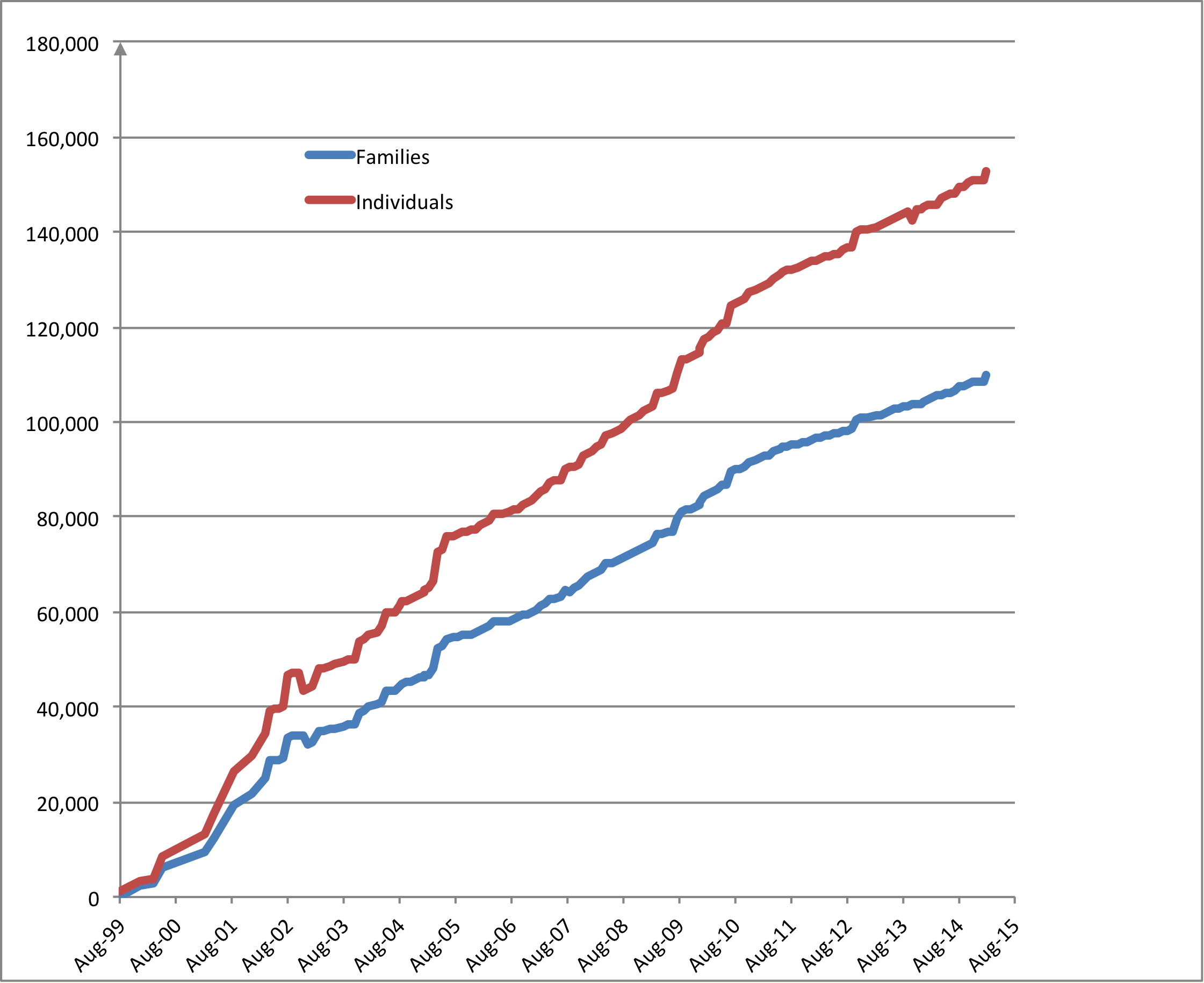

Because the original Farhi tree had grown so much, the website display required new software that allowed dynamic reporting and viewing of the data. New trees are added easily. Under the new database approach, a tree may be viewed by the general public (under privacy filters) or by researchers and genealogists with an account ID and password that permits some people to view private data on the living family members. In addition, the pages may be viewed in several different languages, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish. As of March 2015, the website showed 238,077 individuals in 170,011 different families. Many additional trees and individuals are not shown on the site because of various objections from individuals and genealogists. Table 1 shows some statistics of the published trees that cover these families. Figure 2 tracks the growth of the main tree from 1999 to 2015 in number of individuals and families.

Tree |

Individual |

Families |

Percentage |

Notes |

Les Fleurs de l'Orient |

146,560 |

105,483 |

61.56% |

Main Tree (families from the Ottoman Empire and beyond) |

Codron |

21,760 |

13,119 |

9.14% |

Rhodes |

Brook, Weiner, King, Peixotto, Salzedo, Musaphia |

18,879 |

6,721 |

7.93% |

English, Portuguese and Dutch families |

Karaïtes |

13,520 |

5,045 |

5.68% |

Karaïte families from Egypt, Russia and Crimea |

Nizard |

6,131 |

4,213 |

2.58% |

French and Tunisian families |

Azria & Reynal |

6,110 |

2,719 |

2.57% |

French families |

Hassid |

5,642 |

2,103 |

2.37% |

Salonika |

Foxwood |

4,009 |

1942 |

1.68% |

Aristocratic and royal families in Turkey and Egypt |

Hakim |

4,001 |

|

1.68% |

Some branches included in Fleurs |

Donchin |

3,921 |

1,238 |

1.65% |

Some branches included in Fleurs |

Raymond |

3,041 |

|

1.28% |

Families with Ottoman origine |

Abeski and Ashkenazi |

1,108 |

|

0.47% |

Russisant and Lithuanian families |

Unlinked Families |

981 |

349 |

0.41% |

Families with same surnames but not linked in Fleurs |

Gubbay |

889 |

308 |

0.37% |

Some branches included in Fleurs |

Farhi (other) |

504 |

118 |

0.21% |

Unlinked Farhi found in various lists (1920 and 1930 U.S. and U.K. censuses, Shoah, Montefiore) |

Farhi (Istanbul) |

456 |

310 |

0.19% |

Farhi who married or died in Istanbul from the 1880's to 1980's |

Cicurel (other) |

300 |

|

0.13% |

Families already included in Fleurs |

Farhi (Izmir) |

265 |

182 |

0.11% |

Farhi in Izmir (Smyrna) during the 19th century (extract of records of the Jewish Community (ca 1990's) |

Blum/Heskiel-Coronel/Soria/Taranto |

0 |

0 |

|

Trees (about 200,000 names) are offline |

TOTAL |

238,077 |

170,110 |

|

|

Table 1. Databases of Les Fleurs de l’Orient

The following chart track the growth of the main tree from 1999 to 2015 in number of individuals and families

Figure 2. Growth of the main Fleurs Tree

Major Families

Les Fleurs website includes the genealogy of the major Sephardic families from the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria and the Balkans, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco), UK, The Netherlands, Alsace-Lorraine, Manchester and South Africa.

From Syria, Turkey and the Middle East, we find the following family names: Altaras, Anzarut, Barcillon, Ben zakein, Cattaui, Cicurel, de Picciotto, Dwek/Douek, Farhi, Harari, Jabés, Lisbona, Menashé, Rossi and Sutton.

Based on similar spelling of the surnames, les Fleurs’ major families have about 2,800 Farhi, 1,075 de Picciotto, 850 Battat, 950 Harari and 1,100 Dwek. Levi and Cohen are so frequent that they do not necessarily all belong to the same families.

Website Statistics

Visitors to Les Fleurs de l’Orient website come from 186 countries all over the world but primarily from the United States and Western Europe. The geographic distribution of visitors between April 2007 and March 2015 shown in Table 3, shows the latest statistics on the number of visitors to the website by country of the requests. The website is updated monthly.

Country |

Visitors |

% |

| United States (US) | 25,757 |

33% |

| Israel (IL) | 12,105 |

16% |

| France (FR) | 9,765 |

13% |

| United Kingdom (GB) | 6,602 |

9% |

| Canada (CA) | 2,961 |

4% |

| Brazil (BR) | 1,991 |

3% |

| Australia (AU) | 1,912 |

2% |

| Switzerland (CH) | 1,841 |

2% |

| Italy (IT) | 1,693 |

2% |

| Belgium (BE) | 911 |

1% |

| Other Countries (124) | 11,638 |

15% |

| Total | 77,176 |

100% |

Table 3. Number of visitors by country

Jews of Lebanon

Early on, I came across many Jewish families from Lebanon who had emigrated in the wake of several civil wars and wars with Israel since 1948. The genealogies of these families are linked to my own. The history of these families was provided to the website in a document by the late Ferdinand Nazareth (1917–1997) entitled “Les Juifs du Liban,” written a year before his death (www.farhi.org/ Documents/JuifsduLiban.htm).

Some years later, this article came to the attention of Nagi Zeidan, a Lebanese businessman now living in Morocco. Zeidan was researching and writing a book on the Jewish communities of Lebanon. For that purpose, he had singlehandedly translated numerous Arabic newspapers, electoral lists and death records in order to create a large database and history of Jewish families that had lived in Lebanon until the 1980s. Several excerpts (in French) of his work-in-progress have been published on the Fleurs website under Documents.

Nagi collaborated with Mathilde Tagger and me, as experts in the publication of Jewish databases, and also with Isaac Salmassi and Cecil Dana, both of whom have extensive personal knowledge of the Lebanese diaspora and are familiar with Hebrew and Arabic scripts and languages. After surmounting the suspicions of some former Lebanese Jews about the motives behind his questions, Zeidan befriended many of them on Facebook, with the result that their collaboration created an ever-growing genealogical database of families. The death records database of the Jewish communities of Beirut has been published on Jeffrey Malka’s SephardicGen.com website. The genealogical information of many families also is partially available on Les Fleurs, with the usual privacy restrictions for living people, such as date of birth. The results of Zeidan’s research and my paper on our collaboration was published in AVOTAYNU, Vol. XXVIII, No. 4, Winter 2012 and also may be read on Les Fleurs website (http://www.farhi.org/Documents/The%20Jews%20of%20Lebanon.htm).

The Jews of Lebanon, estimated by Mathilde Tagger at a maximum of 5,000 persons during the French mandate (1923–1943), now are dispersed all over the world. Nevertheless, they remain in close contact via traditional communication links and, more recently, through the Internet’s social network and channels such as Facebook, Yahoo and Google groups, and a private chat room: www.B400.com.

Former Jewish residents of Lebanon now live in Australia, Israel, Europe and the Americas, from Canada to Argentina. They remain a closely-knit, worldwide community with common customs in language (French and Arabic plus their local one), vernacular, culinary tastes, religious practices, family ties and, in many cases, financial success and wealth. Although travel to Lebanon seems unlikely to many, they remain nostalgic for their homeland.

Privacy

One of the greatest controversies about genealogical websites concerns issues related to individual loss of privacy. The large number of individuals and families (including whole trees) who have asked not to be listed on Les Fleurs de l’Orient website reflects these concerns and raises important issues for genealogists.

Fear of identity theft has spawned legislation that differs from country to country, including the European proposal on the “right to forget.” In most countries, the publication of personal data such as date of birth or any personal data for a living person is either prohibited or discouraged. In Australia and the United Kingdom, privacy laws require prior authorization from the person involved before publication of personal data. The United States, however, has no state or federal privacy laws, except for certain limited, specific purposes, but generally accepted practices inhibit the publication of anything about a living person except his first name and family name. In Continental Europe, privacy laws on the books are more restrictive: Publishing anything that could identify a person (including his or her name) is prohibited if the person objects to its publication.

Based on these criteria, on Les Fleurs de l’Orient, no personal data on living persons born after 1914 is visible to the general public. Privacy issues cease with death, and data on deceased persons is published. Any person’s data is deleted upon written request to the webmaster at webmaster @ farhi . org .

“I Cherish My Privacy” Fallacies

Over the many years that the site has operated, I have received many requests for removal under “I cherish my privacy” reasons. All were honored, and the persons’ names and family removed. Fears of privacy breach cited are numerous and related to:

Social Security numbers

Credit card frauds (not to be confused with identity theft)

Identity theft

Job or business opportunities

Prior spouse or marital status

Current profession

Protection of children

Real Reasons for Delisting Requests

After a careful investigation of each request for deletion, I concluded that some requests were unrelated to identity theft and real privacy issues. Instead the implied reasons were to hide origins, religion, or mixed marriages, or to hide from family and associates. Anti-semitism in the country of residence often was mentioned. Others complained of “amateurish” (i.e., not archival research) genealogy as a hobby and the publication of the names of living people.

In a few cases, the reason was stated plainly:

1. “I do not want to be associated with you.” Many requests came from public figures whose professional listings followed Les Fleurs de l’Orient in the Google result page.

2. “I do not want my tree published on your site.” Requests came from people who found their genealogy data posted in the Les Fleurs de l’Orient after having been submitted by members of their own family.

Others were odd requests, such as one that came from a genealogist who had her home address and telephone numbers listed on her own site. Another came from a retired public official in Europe (now deceased) who requested monetary compensation.

In addition to adhering to privacy rules and generally accepted principles of protection of privacy, I also eliminate data that I feel may endanger individuals either in their locale of residence or in their work. Some people live or work in developing countries where knowledge of their religion could jeopardize their status or work. References to indictments and criminal records are also eliminated unless officially published by their family. The same is true of family gossips and feuds, underworld connections or assignments with secret services, such as the British MI6, CIA or Mossad, which may be revealed after the death of the individual concerned. Requests by individuals or relatives are always honored.

Benefits of an Open and Free Genealogy Site

The growth of the Les Fleurs de l’Orient can be attributed to its visibility and the free sharing of data, in which everyone may contribute the results of his or her own research or findings. The publication of information and sharing it free of charge on the Internet is a major part of genealogical research, but we must use good judgment in what we say and publish. Sadly, self-censorship sometimes is needed. Mathilde Tagger would not have disagreed, and she will be missed.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Alain Farhi is a retired businessman with a passion for genealogy. He has been a speaker at several IAJGS conferences and has published articles in AVOTAYNU, Shemot and AJOE (France). Farhi is one of the founders of the International Institute for Jewish Genealogy, administrator of the Sephardic Heritage DNA Project at Family Tree DNA and a member of the Palm Beach, Florida, Jewish Genealogy Society. Born in Egypt and educated in France, Farhi chose the United States as his country of adoption. He is married with two grown children and a year-old granddaughter.